Looking Back: The Story of Nevada’s Birth

Politics, war and silver prompted Nevada’s statehood

Written by Matthew Renda

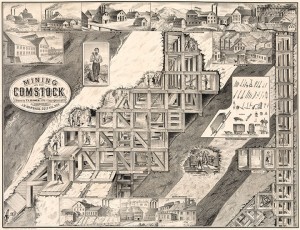

Mining on the Comstock / drawn by T.L. Dawes; engraved and printed by Le Count Bro’s., San Francisco. Image courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

The year 2014 ushers in Nevada’s 150th birthday.

The Nevada Constitution, which was created at a convention in Carson City in July 1864, was sent to Washington, D.C., via telegram on October 26, although the transmission lasted until October 27. The 16,543 words cost a total $4,303 (about $62,000 when adjusted for inflation) and was the longest message ever transmitted via telegraph at the time.

Nevada is alternatively known as the Silver State and the Battle Born State. Both monikers hearken back to its October 31, 1864, inception.

Forging into the Frontier

Nevada is the driest state in the nation, with an average of seven inches of rain per year. The seventh largest state has the unique basin and range topography endemic to much of the western portion of North America. The Great Basin stretches into and covers most of the northern part of the state, while the south includes part of the Mojave Desert.

Nevada’s extremely arid geography accounts for the sparse population both now and in the beginning of the European exploration of the American West, which began in the early part of the nineteenth century.

Early explorers, including famed mountain man Jedediah Smith, punctured the frontier and pioneered trails into the unforgiving terrain that belied the wealth of riches accumulated beneath the soil.

In 1850, the area was part of the newly formed Utah Territory. That same year, Mormon Station was established as a trading post along the easternmost point of the California Trail (which conforms to current State Route 88), marking the first settlement in what is today Nevada. It was soon rechristened Genoa after the coastal city in Northern Italy by Orson Hyde, one of the Mormon leaders of the early settlement. While conflicts between Mormons and other settlers of different religious creeds cropped up during the early portion of Nevada’s existence, it was the Utah War and Brigham Young’s decision to summon various settlers back to Salt Lake City to assist in the conflict that caused a reshuffling in western Nevada’s demographics.

However, what really caused a population shift was the discovery of the Comstock Lode in 1859, which precipitated a colossal infusion of miners, many of whom were flocking from California, where the easy-to-reach golden nuggets had been gleaned a decade earlier. The Comstock Lode is widely believed to be the largest silver deposit in the United States and its role in attracting pioneers and settlers to the state is one of the reasons Nevada is known as the Silver State.

In response, Virginia City ballooned in population, enriching some beyond their dreams while casting out others penniless and down on their luck. Virginia City’s silver boom also prompted the establishment of Nevada as a territory, separate and distinct from the Utah Territory, by bringing a critical mass of population to the otherwise desolate portion of the American West, creating the need for the courts and laws that would one day become the state government.

Political Origins

Like the genesis of most entities as complex and nuanced as the state of Nevada, the truth relating to this large swath of desert territory is obscured by, and intermingled with, myth, legend and embellishment. One such fabrication surrounding Nevada’s birth is that it was granted statehood by the United States of America during the fiercest stage of the American Civil War as a means of funding the war effort by taxing the copious amounts of silver extracted from Nevada’s highly mineralized western ranges.

While Nevada’s entrance into the Union was cemented during the Civil War, by October 1864 the conflict was in its dying throes, with the Confederate Army on the run and in tatters, the Union winning decisive victories at Gettysburg and Vicksburg earlier in the year.

Furthermore, the United States had collected taxes on the silver extracted from Nevada’s mines since 1861, when the Nevada Territory was split off from the Utah Territory for the express purpose of providing funds to the federal government. The government didn’t need Nevada’s statehood to get its cut.

What it did need, in 1864, was Nevada’s electoral votes. Then-President Abraham Lincoln faced the imminent prospect of being ousted from his office just as he was on the cusp of achieving victory for the Union Army and forwarding a domestic agenda that included the abolition of slavery. Lincoln faced off against his former General in Chief of the Union Army, George McClellan, whom Lincoln dismissed in 1862 after general ineffectiveness and a proclivity for paralysis by analysis instead of attacking the greatly outnumbered Confederacy. McClellan ran as a Democrat and promised voters he would end the war and negotiate with the Confederacy as a separate political entity. Another candidate in the election, John C. Fremont, ran as a radical Republican. Fremont appealed to the fervent abolitionists who felt Lincoln wasn’t moving fast enough to end slavery.

In an effort to muster the necessary electoral votes, the embattled President and his supporters attempted to hasten Nebraska, Colorado and Nevada into statehood. Participants in Colorado and Nebraska’s constitutional conventions voted against statehood, leaving Nevada as the only western territory to join the Union. However, Lincoln’s campaign scheme to stack electoral votes ultimately proved unnecessary as McClellan made a grave political misstep when he reversed course on his party’s plan to bring an immediate end to the war.

Fremont, who two decades earlier gained famed as an explorer and as one of the first men of European descent to see Lake Tahoe, agreed to withdraw from the race in exchange for political favors.

Meanwhile, Lincoln thumped McClellan both nationally and, incidentally, in Nevada, easily carrying the fledgling state. An ancillary benefit to adding Nevada was bolstering the corps of Republican representatives in the U.S. Congress, particularly in advance of the January 31, 1865, vote on the 13th amendment, which abolished slavery and involuntary servitude.

After 150 years, much has changed for Nevada—but it retains traces of the Wild West that brought it to life.

Matthew Renda is a Santa Cruz–based writer and editor.

Category: Historic Tahoe, Looking Back