Reno’s Changeover, Redux

The Reno-ssance of America’s Biggest Little City

Written by Brad Rassler

An arch has stood vigil over Reno for nearly 90 years.

It’s the same span that makes an appearance in countless stories about the city, including one composed in 1966 for The New Yorker by the late M.F.K. Fisher, best known for her food writing but widely regarded as one of America’s finest writers. In a short story called The Changeover, Fisher’s female protagonist sojourns to Reno following a long illness.

“On the way to the hotel at which I made a reservation, suddenly there was a flash of almost audible light, and sure enough, I had not forgotten the street of neon and thick gaudy signs with the arch blazing over it. I was in Reno, symbol of sin, of quick divorce and quicker marriage, of unlicensed license…”

In 1966, a visitor to Reno would have beheld the city in all of its neon splendor, with myriad casinos casting a promenade of lights along Virginia Street, from the rail line to the Riverside Hotel on the Truckee River’s south bank. Most of the street’s gaudy glory, however, would have been clustered hard by the Arch itself.

That iconic parabola proclaiming Reno’s littlest bigness remains in situ, of course, but the glow surrounding it has dimmed somewhat since Fisher’s mid-twentieth century holiday. Reno is in transition, and has been for years. The 16-story building sitting at the Arch’s western span at 255 North Virginia—the old Fitzgeralds Casino and Hotel—seems to have gone the way of Reno, and its own narrative arc is perhaps an apt metaphor for the city’s.

CommRow’s Confusion

The “Fitz,” which opened in 1976, initially thrived, but like other properties in town was hobbled by a weak economy and a siphoning of Reno’s gaming revenues from California’s casino boom. The building was purchased in 2007 by Donald Wilson, the owner of a Chicago commodities trading firm, who sought to repurpose the property when the Fitz failed, which it did the following year. The property remained dark for nearly two more years until Wilson and his managing partner, Fernando Leal, settled on a plan for it.

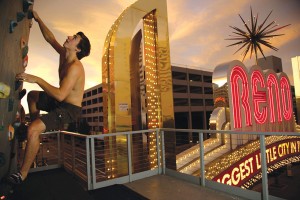

Months before its 2011 grand opening, Leal heralded CommRow—the property’s new moniker—as Reno’s first non-smoking, non-gaming boutique hotel. When CommRow’s doors swung open in October of that year, the public beheld a semi-finished interior sporting a conceptual mashup seemingly hatched from a fever dream: Along with a ground floor food court, the property contained a handful of bars, two concert halls, a dog-friendly lobby, a coffee shop and a climbing gym with a 165-foot outdoor wall whose ramparts overhung the Reno Arch. Nary a hotel room was available for rent.

CommRow confused more than it amazed, and people mainly stayed away. Within a month of its grand opening, Leal shuttered it “for remodeling.” It reopened, but then closed again—this time, for redesign. When it reopened again the public learned that Leal had forfeited the keys to Wilson and lit out. New management was brought in to salvage the concept, but to little avail. The climbing concept survived, but nothing else.

“It was a saga,” says Brian Sweeney, manager of BaseCamp, the climbing gym. “The running joke was that if we’d had a reality TV crew filming all along, we’d be millionaires by now.”

The new crew worked hard to resuscitate CommRow, Sweeney says. “They did a ton to throw lipstick on a pig. But CommRow was set up to fail; they couldn’t do much with it.”

Wilson, who is apparently a fiercely competitive sailor and is said by his managers to care deeply about the sustainability of his Reno investment, held fast to 255 North Virginia and an assemblage of properties on the same square block. He hired consultants to analyze the hotel market and to reposition the property. In 2013, his company, DRW Holdings, announced that Comm-Row would become the Whitney Peak Hotel, Reno’s first luxury boutique concept. The 158 rooms on the hotel’s upper floors would be renovated. The climbing gym, with its world-class outdoor wall, would remain, as would one of the concert halls. The ground floor would be occupied by a full-service locavore restaurant and bar. The new tagline (because there’s always a tagline): “Bringing the outside in.” The grand opening is slated for June 2014.

Wilson poured an additional $10 million into the property, closed on an adjacent 1,000-space parking garage owned by the City of Reno, and swept the country for a general manager who could breathe life into the place. Meanwhile, he negotiated a partnership with Mark Estee, the renowned chef and restaurateur whose award-winning eatery, Campo, has helped put Reno on the foodie map; Estee agreed to take ownership of Whitney Peak’s 4,000 square foot restaurant, and the project took on a new life. The search for a GM ended in January, when Rob Hendricks of Joie de Vivre Hospitality accepted the job. A protégé of JdV’s charismatic founder, Chip Conley, Hendricks says he channeled Conley’s entrepreneurial spirit and dove in.

“It’s an amazing challenge, probably the biggest one I’ve ever had in my career,” says Hendricks. “I really feel like I’m the person that belongs here. I mean, it’s just this crazy place, and it needs a crazy man. I’m one of those people that really seeks the purpose and the meaning in what I’m doing.”

Bootstrapping a Better Reno

Seeking purpose and meaning in what one is doing: That sounds like a lot like Reno in 2014. There’s much at stake for the city and its preternaturally optimistic citizens based on the moves they themselves choose to make in the next few years.

Within the last six years, Reno’s unemployment rate hit 13 percent and housing values dove 50 percent. The city, which always suffered a sullied image, now found itself the butt of national jokes, branded as derelict and low brow, a place of “lasts” and “firsts”: Divorce, easy marriage, a place to light out from, a place where one could quietly lose one’s hard-earned savings or one’s life, for that matter, a place for people to live their remaining years after making their fortunes elsewhere. Nevada ranked last of the 50 states in high school graduation rates and first in foreclosures and unemployment.

Reno’s residents, however, were having none of it. Matriculation at the University of Nevada, Reno, continued to swell despite budget cutbacks; its schools of science, buttressed by the world-renowned Desert Research Institute, brought major projects to town: unmanned automated systems (drones), nanotech, a world-class earthquake lab. Californians immigrated to Reno from the Golden State, but did so for the laid-back pace, lower cost of living and outdoor lifestyle. As Burning Man’s Black Rock City grew each year, so did Reno’s sizable creative class. Urban micro farms emerged, as did craft breweries, a thriving food culture, a new museum, a bike co-op and strong grassroots environmental groups. An entrepreneurial and startup community formed downtown. The national press took notice: Outside magazine lauded Reno’s downtown whitewater park and UNR’s quality campus life; Esquire magazine gave props to Estee’s Campo restaurant and The New York Times wrote about the renewal of Reno’s Midtown District. The town bootstrapped its way to a better place.

“Reno is growing organically rather than being stimulated by huge outside investment,” says Bill Thomas, Reno’s assistant city manager. “The entrepreneurial class is telling us that the less help they receive from the city is actually ‘more.’ Everything’s going well without us.”

Well, maybe not everything. With empty or upside-down coffers in its downtown redevelopment districts, large tracts of the city have gone untended, allowing longtime property owners with few encumbrances to cash flow, with no practical incentive or taxes to cause them to upgrade their real estate. Those economics in part explain Reno’s patchwork pockets of prosperity, with neglected properties rubbing shoulders with those already repurposed (ironically, Wilson controls nearly a third of the square block on which Whitney Peak sits, and the majority of the storefronts are currently dark, but with plans to lease them, as has been done with the newly renovated Siri’s Casino also near the Virginia Street arch).

“We view the city as essentially a living organism,” says Eric Raydon, a principal of Marmot Properties, a real estate development firm specializing in adaptive reuse. “If you have poorly lit, poorly maintained and functionally abandoned properties, whether it’s a building or a lot, those are like dead tissue. If you don’t cut it out, it will make the rest of the body sick or even kill it.”

Extending that biological metaphor, Whitney Peak is nothing less than a reanimated corpse. Positioned at the center of the city’s core, on its only honest-to-goodness main street, and by the arch M.F.K. Fisher celebrated many years ago, Wilson’s project undoubtedly represents the most significant northern outpost of the non-gaming “Reno-ssance” inching inexorably toward UNR; the town’s eventual intellectual and physical union with the university is deemed by government officials, business leaders and academics as critical to Reno’s future prosperity. “A university town rather than a town with a university,” as Renoites have learned to say. And though Whitney Peak resides within a sub-range of monolithic casinos with faux street fronts and windowless, Escher-esque interiors designed to obscure the exits, the current incarnation of 255 Virginia, like CommRow before it, has clearly positioned itself as anti-casino, catering to a clientele that won’t think twice about shelling out $150 for hip center city accommodations boasting climbing facilities, concierge-level service, a view of Mt. Rose unhindered by the scrim of cigarette smoke, lobbies freed from the chirp of gaming machines and a healthful milieu fostering relationship building with members of their own well-educated and active tribe.

“This property is kind of a billboard for Reno,” said Wilson’s owner’s representative, Mat Meadows, in an interview late last year. “This is the new Reno.”

And it would seem that Reno, with its aspirations to jettison its intemperate past and embrace its salubrious future, enrich its innovation and environmental ecosystems, harvest its intellectual and natural capital, and luxuriate in its joie de vivre and je nes sais quoi… well… Reno may well be the new Whitney Peak.

“The sun would be along soon, and meanwhile I knew I was not ill anymore,” writes Fisher’s character in The Changeover’s coda. “The divorce had been granted. I had complete custody over myself.”

Brad Rassler is a Reno-based writer and owner of the environmental consulting firm A Sustainable Way.

Category: Current Issue